“When I played it back I thought, ‘This is OK actually, maybe I should release it.’ All the technical aspects of the recording were just right, too, not a single fault. I didn’t have to change anything. It was perfect.”

-Manuel Göttsching

Anyone who has ever picked up an instrument and spent time improvising, either by themselves or with additional musicians, will know of the feeling when a particular session comes together in a way as to feel complete—the feeling that the creative motor fires on all cylinders, and the physical execution rises to meet it. It’s what all musicians strive for: the convergence of skill and taste.

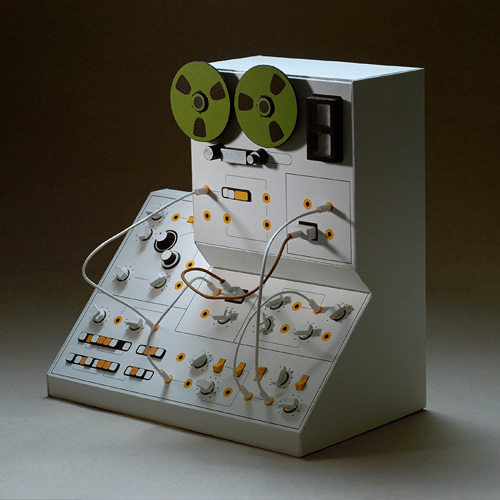

And hallelujah for the times the recorder was running! In the case of Manuel Göttsching’s E2-E4, not only was it running and set up to capture the session, but in a premonition-like stroke of luck, Göttsching proceeded as if he were to officially record a studio session.

Hindsight is 20/20 as they say, and how many times has a musician—at the end of a particularly sparkling session—exclaimed, “oh if we had just recorded that!”? To Göttsching’s surprise, and our good fortune, he did!

Prior to and during the time of the recording, Göttsching was captivated by compositions by prominent minimalists, such as Terry Riley and Steve Reich. His own work in Ashra (Ash Ra Temple) had grown progressively more electronic, incorporating loopers and synthesizers. He pushed Ashra, which by now was more a solo act than a group, from its early krautrock/progressive leanings into the forefront of electronic music.

Ever the guitarist, however, he began layering his guitar over the top of slowly morphing synths and gently-looped beats, and albums such as New Age of Earth, Blackouts, and Correlations would feature looped, treated guitar. This would continue to be his MO through much of the mid- to late-70s, leading up to the recording of E2-E4, when he began to experiment more with drum machines, sequencers, and synths.

The story, according to Göttsching, is that he wanted to record some music to listen to during a flight he was taking the next day. The result was a one take, hour-long piece whose foundation was a repeating synth riff over which he added some rolling electronic high hat and light, steady bass thumps. The centerpiece of the work—some lovely improvised guitar—enters the mix around the halfway point.

The album functions well as either background music or, arguably more so, when the listener is actively listening. It shines brightest through headphones and especially if said headphones are of higher quality and driven by decent audiophile equipment. That’s not to say you have to have higher-end equipment to enjoy the album. Its ability to grab the listener and take them in is mostly due to the structure of the piece itself, rather than the production quality.

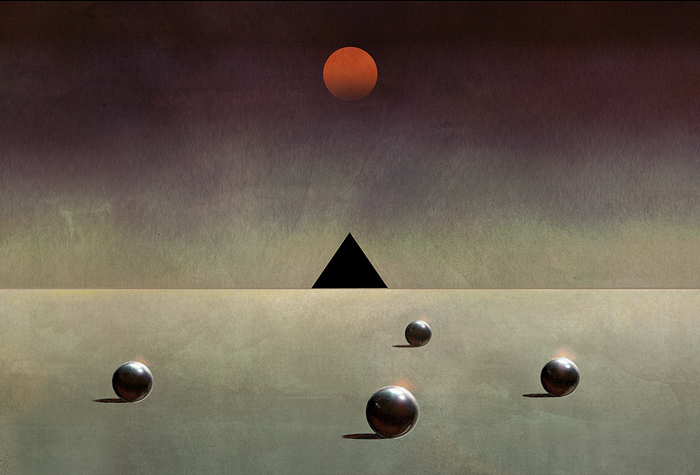

Repetition is key here. It lends a stability to the piece that grounds it while at the same time allows it to transfix the listener. While it does on one hand somewhat point to the fact that this album was recorded spontaneously, it doesn’t come off as an unintended result due to the brevity of recording, or as the limitation of one man being at the helm. At many points, it keeps the piece from spiraling out from itself.

Take for example around the 47 minute mark. Göttsching’s guitar playing here has intensified, and begins to spread out. You can feel him pushing himself to let loose and fully explore how far he can take it within the confines of the song. It’s at this moment where his guitar comes as close to frenzied as it will within the piece. He feels like he’s getting ready to take off.

It is the foundation of the sequenced synths that keeps him in check. The interplay between this steady, structured base and the reaching, escaping guitar creates a beautifully strained and dichotomous pairing. It’s the climax of the album and it’s hard to resist bobbing your head along to it.

Göttsching has said that he didn’t immediately know what to do with this album after he had created it. He played it for Virgin managing director, Simon Draper, who liked it and referred Göttsching to Virgin Group founder, Richard Branson. He also liked it. Yet because of Göttsching’s reluctance to release it on Virgin to avoid it getting lost in a sea of mainstream releases now regularly coming through the label, it sat on the shelf until 1984.

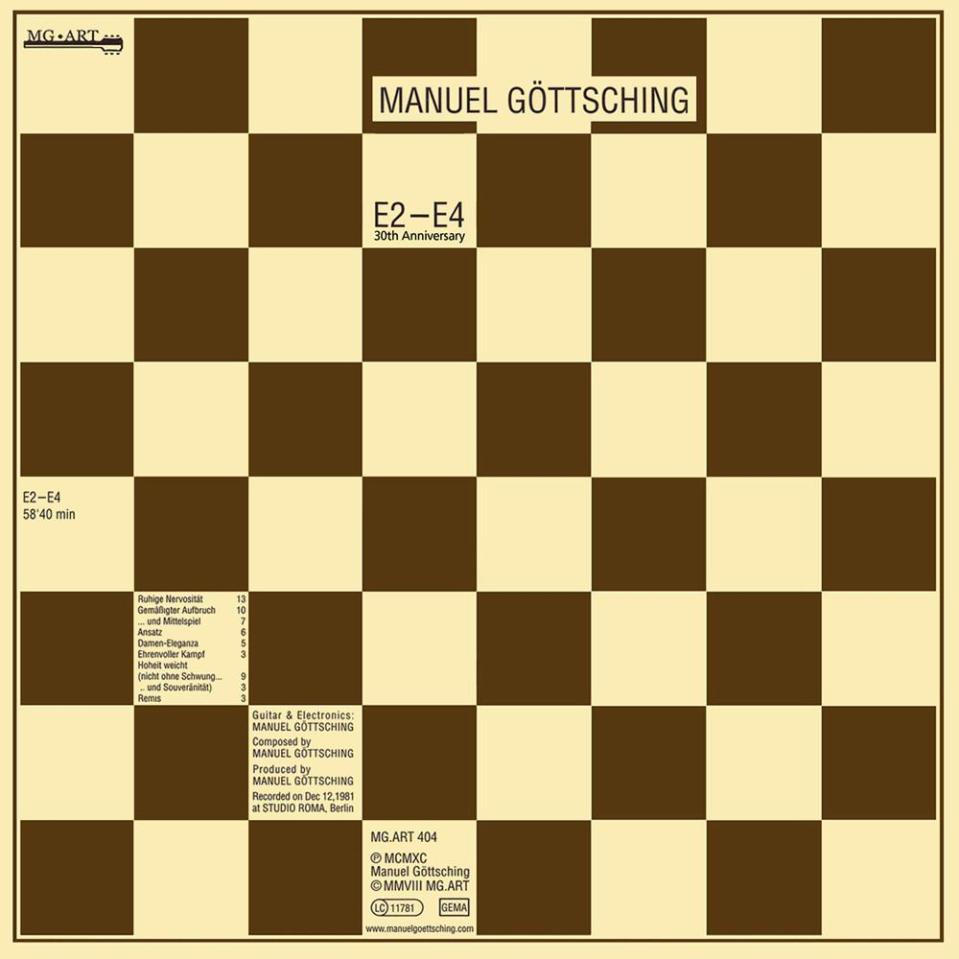

He finally released it as E2-E4, a nod to both chess and R2-D2 (whose technical-sounding name he appreciated), on the smaller Inteam label. Its first run was 1,000 copies. The reception was modest, and it quickly faded into cult status.

It has maintained an influence, however, on electronic artists since its release. And while it’s certainly not widely known outside of the music industry and electronic music aficionados, it is undoubtedly considered a work of high achievement to those in the know. It is lightning in a bottle, or more precisely, on tape.

You can purchase E2-E4 at the official Ashra shop here.